As micromobility matures, controversy turns into collaboration

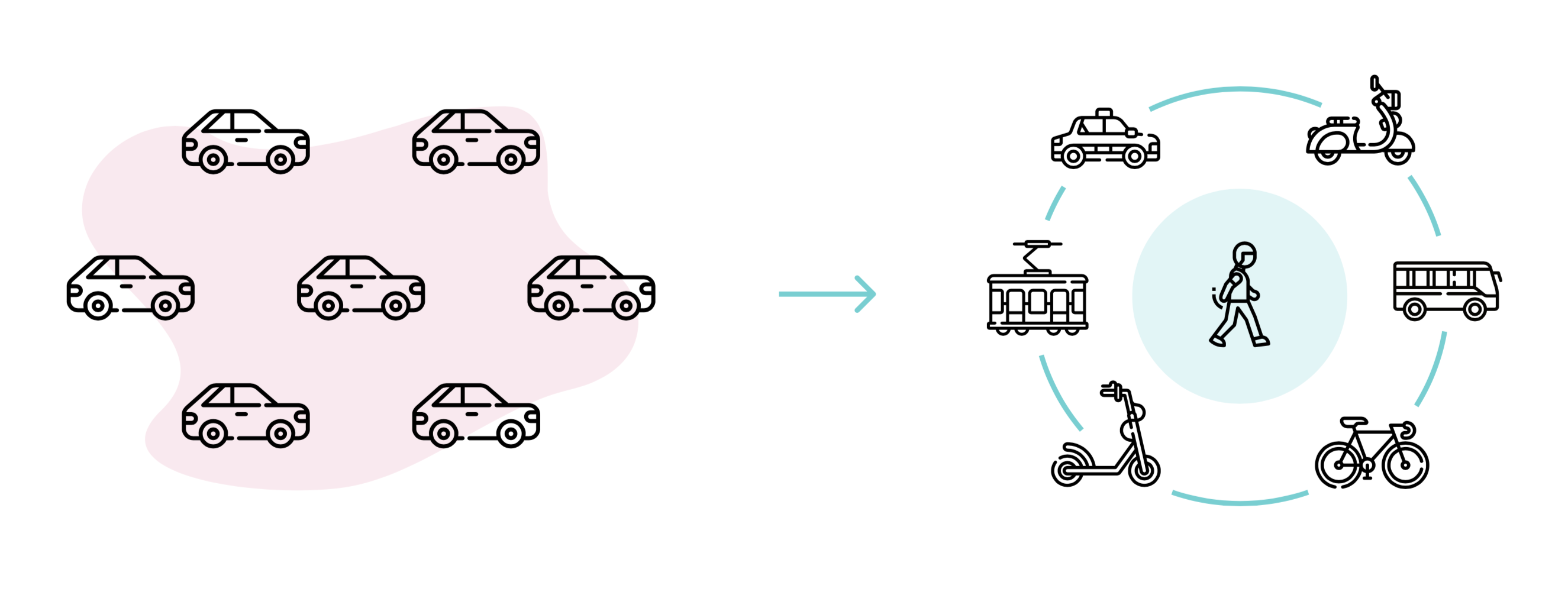

Micromobility plays a major role in a wider and profound disruption of the whole mobility ecosystem. Its successful integration into our pre-existing mobility networks will have a major impact on our lives, cities and environment.

This article is part of Finding the way forward, our publication focusing on new mobility in the age of data, platforms and ecosystems. Download the publication here, and learn more about our approach to the mobility industry here.

From e-scooters to shared bikes to electric monowheels whizzing past us silently and effortlessly, micromoblity is here to stay. When used in combination with existing choices like public transportation, taxis, bicycles and walking, it offers a seemingly emission-free and fast way of completing daily journeys.

Micromobility covers various types of small vehicles intended for personal use over relatively short distances and particularly in cities, ranging from regular bicycles and scooters to their electric counterparts and beyond. The phenomenon itself is not particularly new, but the term has recently spiked in popularity with the emergence of e-scooters and -bikes, as well as a variety of new rental and sharing services built around these vehicles.

The use of shared modes of mobility was already skyrocketing before the Covid-19 pandemic. While the development has temporarily slowed down, shared mobility is projected to represent 16% of all global travel by 2040, clocking in at an impressive 4,250 billion kilometres. That’s over 100 million laps around the world.

These new modes of transportation continue to grow because they are convenient, easy to use, and fun. And they are what people want. By working together with the users to understand their needs and wants, micromobility companies have scaled up at an unprecedented pace, introducing their services to new cities and countries in record time.

Due to the complicated nature of massive transportation systems, all involved parties must collaborate to create the change we need: the private and public sectors; the regulators and the citizens; the end-users and service providers. All must work together for a common goal.

Cities – and travelling within or between them – have evolved over hundreds and thousands of years. Changing the way we move means changing the cities themselves, and this will take time.

Collaborating for the common good

Ubercab, as they were originally called, launched their first commercially available service only 10 years ago. Since then, UBER’s disruption tactics have led them to become one of the most hailed, and many times most hated, new mobility service providers. The company was valued at over 80 billion USD at the time of their IPO in the spring of 2019 but crashed to half of that in 2020 (and has since recovered).

After the early days, Uber has become much more collaborative, working with cities and regulators, and even at times partnering with former competitors to be able to exist in certain markets.

In Europe, cities and governments aim to provide citizens with transportation options that help make cities livable and thriving, both now and in the future. Choices used to be limited to public transportation (busses, trams, trains) and private cars, but since the advent of Uber and the emergence of other new modes of transportation, transport officials have had to start discussing, planning and collaborating with a variety of new service providers entering their streets.

As they have matured, the new service providers have also realised that they need the city as a whole to function in order to provide a good service for their users. The early days of Lime e-scooters littering the streets and sidewalks of San Francisco did not work, and the end customers – the people living in the cities – were not better off. But the early success proved that people wanted more and quickly adopted new modes of transportation.

For mobility services to thrive in the long term, the parties involved must set new rules for a new era of mobility. Commercial, regulatory, technical and even branding questions need to be agreed upon. Due to the massive size of the ecosystem and the complexities involved, it’s clear that nobody can just follow their own agenda or protect their positions. Collaboration is the only way forward.

Win-win-win ecosystems

For many organisations, this calls for new and unusual ways of conducting their business. In the context of the wider mobility ecosystem, the rules of traditional business models may not apply anymore. There are different factors to consider when working in, or building, an ecosystem. It needs to provide all stakeholders with a win-win-win proposition, and the sum total needs to be positive – greater than its parts on their own.

Ecosystems are based on trust, not lock-in agreements and terms, and end-users must have easy access to their service of choice. Technical compatibility as well as clear rules for managing and sharing data are a must, and fighting for customer ownership will undermine the ecosystem. The collaboration between established mobility services and new mobility solutions is inevitable, but also a massive undertaking.

At the end of the day, the success of new modes of mobility, or new mobility ecosystems, depends on the end-users. If they don’t like what they see, they can easily get back in their cars or choose other means of moving around.

Understanding the customer is where service creation and ecosystem building should start.

Designed with resources by Freepik.

Designed with resources by Freepik.

Understanding user needs

When the automobile was launched, Henry Ford used the promise of free and open highways for everyone as the ultimate prize for buying and owning a car. That promise still echoes in all automobile advertisements. But the reality of the ensuing congestion and pollution, and the ineffectiveness of that paradigm in today’s world, has led to a need for new solutions.

Freedom of mobility – travelling when you want to and where you want to – is still what people look for in mobility solutions. Reaching that freedom now needs to take new forms in the face of the massive number of people travelling in cities, and beyond, every day.

When asked directly, people will have a hard time expressing their wishes for new mobility solutions. Had Mr. Ford asked people what they want, the answer could indeed have been faster horses. But, when exposed to actually using – or at least imagining using – new solutions in their daily lives, potential issues are quickly spotted and promptly solved. This is one of the cornerstones of user-centric service creation, employed by our Lean Service Creation methodology.

For example, when people are asked how many trips they take per day, how many kilometres they travel during these trips, or even how long they travel – they don't really know. Travel patterns are automatic and deeply ingrained. That is actually an advantage when designing new mobility solutions, since it turns out people mostly don’t change their habits.

In Finland, people take around 3 journeys per day, for a total of around 40 kilometres per day, and this has remained the same for a long time. In London, for example, the number of trips per person stays similar, but the time spent stuck in traffic may be different. When journeys require new multimodal solutions – i.e. combining one option with another – things get more complicated, and users need to be nudged towards making an effort and changing their habits. There is slow but certain change towards more sustainable choices, as the 2020 Travel in London report suggests.

One part is understanding the needs of the users (e.g. travelling from point A to B) and the potential obstacles users feel they might face if they change their travel habits. These can include things such as:

- the inconvenience of switching between modes,

- insecurities related to unknown routes and schedules, or

- confusion related to costs.

The goal needs to be solving actual user issues and giving them enough reasons to embrace new choices in their daily mobility habits. The benefits of choosing new ways need to be clearly communicated while giving the users what they need: freedom, comfort, predictability and control over their movement.

The future is here – let’s face it head-on

There is no stopping the future. The way we travel is going through more radical changes now than it has over the past 100 years. The change is spurred on by our need to cope with the number of people moving in cities, the burden mobility places on the environment and people’s desire for choices, comfort, convenience and sustainability. Transportation is one of the biggest, most complex systems on the planet, so there are opportunities and challenges for all.

Micromobility and its unparalleled ability to solve the problem of the last mile is an integral part of this future. With open and honest collaboration where end-users, solution providers, and cities and governments together figure out the best way forward, we can all win.

We do this by understanding the end customer, the technological challenges to be solved, the needs of larger systems like the cities, and being able to agree on issues such as data sharing, customer ownership and commercial rules and models. In other words, we win by building collaborative ecosystems.

The way to get started is to simply open a dialogue, bring the relevant parties together, and ask for guidance where needed. Often the use of external experts, facilitators and builders of business and technology ecosystems is recommended – or required.

Are you ready to face the future head-on?

Our key takeaways on multimodal mobility

- Cooperation is paramount – all the players involved need to find common ground.

- Understanding the end-user comes first, and services must be built around their needs.

- Mobility is complex, and the ground rules of ecosystems are evolving to adapt.

- The shift towards new multimodal mobility is inevitable – not something that may happen.

The model city for sustainable urban mobility

Expert interview with Anna Huttunen, Project Manager for Sustainable Mobility at the City of Lahti, Finland

Lahti – the ninth largest city in Finland – has been focused on environmental sustainability all year as the 2021 European Green Capital. In addition to pursuing ambitious goals like carbon neutrality by 2025, the city has also conducted a personal carbon trading experiment in an effort to promote sustainable choices in mobility.

In this interview, Anna Huttunen, Project Manager of Sustainable Mobility from the City of Lahti, reflects on sustainable mobility from the public sector point of view.

Photo: City of Lahti

Photo: City of Lahti

What are the cornerstones of sustainable urban mobility from the perspective of a city?

It all starts with having ambition, a goal, and the desire to change – but you’ll also need strong ownership and careful planning to succeed.

Additionally, you’ll have to accept that road space has to be distributed differently to make sustainable modes of transport safer and more attractive than other options. Environmental impact and public health benefits must be a priority in urban planning and land use.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of “If you build it, they will come” – if the aim is to encourage more people to commute by bicycle or on foot, your infrastructure has to support that goal.

The recent experiment in Lahti focused on personal carbon trading (PCT) in mobility. What were its biggest takeaways, and does it seem viable on a larger scale?

Absolutely – I believe PCT could be an alternative to certain direct carbon taxes and it can play a big role in the future. It will definitely require more research, but it’s worth researching. Ideally it should also cover other aspects of life, like your dietary and residential carbon footprint.

Through the experiment we managed to bring PCT back into public discussion, generate valuable real-world data for research purposes, and support similar initiatives elsewhere. Our experiment focused mainly on making emissions visible – gamification could be a way to take it further and gain even more traction.

How can cities foster positive attitudes towards sustainable mobility?

From the urban planning point of view, involving citizens early on is a good way to improve the outcome and reception of new initiatives. It can also provide insights that help you justify decisions along the way.

Beyond that, it varies. The health aspect resonates well with some, many find the environmental angle important, and others respond well to pricing incentives. Promoting the idea of sustainable mobility is a combination of many things – I think of it as a marketing and communication effort.

What is the role of partnerships in all this?

Cities are responsible for enabling smooth and functional mobility options for their citizens, but the execution can be a combination of public transport and privately operated shared modes of mobility. It hardly makes sense for a city to directly own and maintain a fleet of city bikes.

Private sector partnerships play a key role in this. Especially when new modes of transport expand more rapidly than laws and regulations, communication needs to be active, open and transparent. The most efficient option would be to hold these discussions as a roundtable between several cities at the same time.

Learn more about our approach to the mobility industry here.

Kaj PyyhtiäPrincipal Advisor

Kaj PyyhtiäPrincipal Advisor